![]()

The Impact of Electronic Document Management Systems on Technical Writers' Job Duties

By William Cracraft

May 2003

Table of Contents

Executive Summary………………….2

Introduction…………………………....3

The birth of

EDMS

EDMS today

Four types of EDMS…………………4

Basic EDMS

Archival EDMS

Commercial EDMS

Industrial EDMS

Applying the Information……………9

Preparing for an Interview

Conclusion

References……………………………11

Executive Summary

Electronic document management systems

(EDMS) consist of an electronic repository where documents are stored for easy

access by multiple users. EDMS also provide formatting and security parameters

for accessing documents. EDMS have been developing for about 20 years and have

now become quite sophisticated. These combined traits have made EDMS indispensable

to technical writers and their employers. The two main parts of an EDMS are

the repository and authoring tools. There are four main types of EDMS in use:

basic, archival, commercial and industrial.

Basic systems are used in many small companies. These systems are homemade and the repository is usually just open server space, while the authoring tool can be anything users choose. Archival systems are usually associated with universities and many have been developed in-house. Though large, academic archive content is often static and most of the publishing work is in formatting and cross-referencing documents written by contributors. Commercial systems are solutions developed for sale. Companies who routinely produce documentation use commercial systems, which provide a secure, structured repository and a specific set of authoring tools. Industrial systems are very robust, highly customized systems for use by governments or for large projects. These systems usually have very specific features developed for the purchaser and may be designed for use with one main authoring tool. FrameMaker seems to be the authoring tool of choice for commercial and industrial systems, but there are a variety of companies providing electronic repository services.

EDMS are technical writers' working environments. EDMS are the primary tools used for creating extensive documentation, and a good EDMS greatly simplifies workflow, saving time and money. Technical writers should familiarize themselves with the four types of EDMS and when interviewing in order to ask intelligent questions about the target company's system. Technical writers are likely to become subject matter experts on EDMS as commercial systems become more common. Understanding how to best exploit EDMS technology can add significantly to a technical writer's value in the job market.

Introduction

This paper presents the results

of an investigation into the impact electronic document management systems (EDMS)

have on technical writers in their work. EDMS are probably the greatest addition

to technical writers' toolbox since authoring software came into widespread

use. EDMS are used to store scientific papers, author instructional documents,

and create and maintain a host of other data sets. In each case, those moving

documents in and out of EDMS are technical writers in one sense or another.

This paper contains a brief history of EDMS, an overview of contemporary EDMS

illustrated by four examples, and a summary of how technical writers can prepare

to discuss EDMS in an interview.

Birth of EDMS As soon as two computer users decided to share a single document file, EDMS were born. The next step was to deliberately create centralized file space for use by employees. These nascent EDMS networks sprouted with the technology boom. EDMS of the mid-80s were often handcrafted systems running on industrial strength computers at a universities and large technology companies. In the mid-90s, all technology companies, large or small, had the capacity to organize central repositories with separate areas for sales, marketing, accounting and engineering departments. By the late 90s, industrial-sized EDMS became commercially available. EDMS have now come full circle and are available as industrial strength servers with highly customized and flexible software.

The growth of EDMS added a new dimension to the duties of technical writers. The EDMS is to technical writers what the lathe is to a machinist or the workstation to an engineer. It is the hands-on tool in technical writers' working environment. Many people touch the EDMS, but technical writers use it as a primary tool-to publish documents.

Technical writers will find a variety of EDMS when they start new jobs. A good rule of thumb is the greater the number of computer users at a company the more sophisticated the EDMS is likely to be. Naturally age and configuration will affect the quality of the EDMS. The $64,000 question is what can technical writers do to prepare for working with an EDMS? The answer is to learn about EDMS in general and about specific systems whenever possible. The remainder of this paper will give an overview of EDMS in the workplace and some examples of what organizations are using today.

EDMS Today

EDMS applications "focus on the control

of electronic documents, document images, graphics, spreadsheets, word processing

files and complex-compound documents through their entire life cycle," (Bielawski

and Boyle 1). As complicated as that definition sounds, EDMS can be very simple.

One computer acts as a repository for the documents, users at their own computers

can access the documents and changes are uploaded to the repository.

Repositories are anything from open server space to highly structured, secure commercial software installations. In all cases, repositories are essentially large capacity data storage spaces that contain and control documents and associated information (Bielawski and Boyle 63).

The documents in EDMS repositories can be stored as Word, Excel, Dreamweaver or any other type of file. These software programs, called authoring tools, should be selected based on the final publication requirements, and audience needs generally point to the best software choices (Bielawski and Boyle 119). Highly sophisticated EDMS will have only one or two authoring tools chosen to accomplish specific tasks. Thus, an electronic document control system consists of a repository and associated authoring tools used to create content available to multiple users operating under a set of protocols that ensure consistency and security.

Four Types of EDMS

Basic Systems

Basic, homemade EDMS are the norm

at many small companies. The EDMS at Omniva Policy Systems, a 30-person software

company for which this author worked, is simply reserved space on a server accessed

through the company intranet. Virtually everyone in the company creates or alters

documents on a daily basis in whatever authoring program is required. Each department

has a pass-protected folder and a general storage folder. Employees also have

personal server space for storing non-public documents. Using a browser, employees

click to the folder needed. Files can be dragged and dropped to the desktop

for alteration, then saved to the server. Using the system is as easy as accessing

folders within a desktop. This document management system is for general use,

has no user-specific functions, and any software can be used for authoring.

For an experienced computer user the learning curve is short and flat-a few

hours at most. Technical writers joining small companies using basic EDMS will

require some information on how documents are stored in the repository, but

authoring tools should be familiar to them.

Archival Systems

Academic archives are among the most

common EDMS. In the early days of computing, universities had both the need

and computing resources to construct large archives. These archives are quite

different than those found in commercial organizations. University archive content

is largely static-changes to documentation are not the norm-but the information

does have to be carefully formatted and cross-referenced, and the archive must

be complete, reliable and accessible from around the world (West).

Stanford Linear Accelerator Center has an archive of learned papers and conference articles associated with its work. The electronic publications department under Sharon West, electronic publications manager at SLAC, gathers papers written by SLAC scientists scattered across the globe and ensures they are posted to a universally accessible archive and cross-referenced in Stanford's SPIRES document database for high-energy physics (http://www.slac.stanford.edu/spires). Many users have access to the articles, but virtually no changes to content are made after posting, and the archive acts as a long-term storage facility (West).

The SLAC EDMS, designed and built in-house, is based on older technology. The system has been around for over a decade and works just fine-articles are available in a few seconds-but the database requires very specialized programming skills for proper maintenance and cannot be upgraded readily due to lack of compatibility with new programs. Electronic publications department workers are used to the system, but their jobs are impacted by the outdated technology. The electronic publications crew spends a lot of time hunting down papers that could have been captured automatically by a more sophisticated system, according to West.

Although the electronic publications group handles a lot of documents, they do very little actual writing. Instead, the group acts as a clearinghouse for documentation written and read by scientists around the world.

SLAC electronic publications workers handle 30 to 50 new articles per month. When the group is notified of an article in the pipeline a document number is assigned and pre-print publication rights are established. Articles coming into the SLAC electronic publications group generally arrive in a special word processing language called LaTeX (pronounced lay-tex). Since authoring takes place outside the electronic publications group, workers spend time checking for formatting errors, verifying citations and converting the documents to PDF files. The PDF files are plugged into an HTML template, some metadata is added for identification purposes, and the articles are posted to the web archive. Next, the group updates the SPIRES database so researchers can find the article. Finally, the library is notified of the posting and catalogues the document. The paper is then part of the active archive (West).

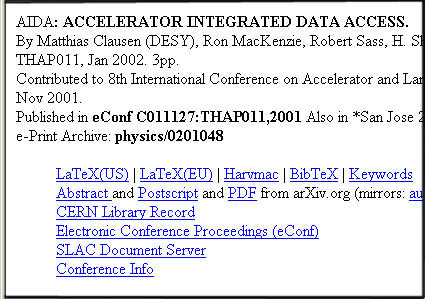

SPIRES

database listing of an SLAC archive article. Note the careful formatting and

the number of cross-references.

SPIRES

database listing of an SLAC archive article. Note the careful formatting and

the number of cross-references.

The SLAC archive started out on a now-outdated VAX computer and there it remains. VAX computers were industrial strength computers introduced by Digital Electronics Corporation in 1977 and phased out in 1992 (Lowe and Arevalo-Lowe). The SLAC system is powerful, but old and highly customized, so finding programmers to work on it is difficult.

The SLAC electronic publications group is looking at a new document intake process in which authors have one point of entry for registering and submitting papers. The group has studied commercial solutions, but cost is prohibitive (West). Since the SLAC EDMS is mainly used for storage and retrieval, not revision and printing, SLAC can get away with the current system as long as it can find someone to service it.

The SLAC electronic publications group is able to function with old technology because the demands are not highly specialized. The repository need only be stable, available, and searchable. The authoring tool is not very important because the electronic publications workers interface to format and cross-reference documents before uploading to the archive. Technical writers maintaining archives such as those in a university environment will likely need to train specifically to use equipment and software at each facility.

For-profit companies have much different needs, thus technical writers use much different skills. In commercial environments, technical writers use specific authoring tools requiring specialized EDMS. All documents will be created using FrameMaker, Word or some other commercial word processing, authoring or layout program, and protocols will be in place for naming and storing documents.

Commercial Systems

Companies who produce documentation

to accompany products have specialized, but not uncommon EDMS requirements.

Coupled with a repository, good authoring software can make production of multiple

or large documents considerably easier. There are a number of commercially available

EDMS solutions for producing good documentation.

Lucent Technologies produces telephony equipment and manuals that support the equipment. The Lucent EDMS is used to archive the manuals while being written and store them after publication, according to Sara Shopkow, former senior technical editor at Lucent in Santa Clara. Manuals are revised in cycles and have finite lives, and new works are always in progress. Final documents are published on the web in printable form, periodically revised and eventually phased out.

Lucent uses a combination of commercial solutions for its EDMS. Manuals are written in Adobe FrameMaker and uploaded to a repository engineered by Documentum, Inc., of Pleasanton. A third company, DataLogics, of Chicago, makes a special plug-in called FrameLink that allows FrameMaker to communicate with the Documentum repository smoothly.

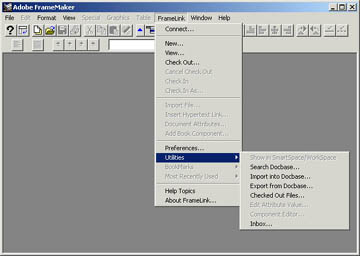

FrameMaker

with the FrameLink plug-in installed. The plug-in adds new functions in the

familiar drop-down menu format.

FrameMaker

with the FrameLink plug-in installed. The plug-in adds new functions in the

familiar drop-down menu format.

The Lucent technical publications group maintains about 15 manuals of 100-350 pages each in their EDMS. Although the system is customized for Lucent, many companies use similar configurations. This user-friendly system allows technical writers to access documents even if others are using the file, exchange appropriate files with engineering groups and maintain the finished manuals in the EDMS for correction and revision (Shopkow).

The system is simple and pretty intuitive, though the learning curve was steep when the system was introduced. The trickiest issue was keeping file names straight because clear naming protocols were not established immediately (Shopkow).

From technical writers' point of view the system is great. Paper files are all but eliminated, peer reviews take place electronically, the security of the system ensures files are not altered outside the group, and printing book-length instruction manuals is easy. The system is commercially available and many companies use FrameMaker, so technical writers are likely to have some experience with at least that part of the system. In addition, knowing how to use a system like this is likely to be of value at the next job.

Industrial Systems

The highest evolution of EDMS to

date consists of large customized repositories combined with specific authoring

tools in order to create extensive specialized databases. The Anzac Ship Project

publications are a collection of repair and maintenance instructions for a complete

class of ten ships built by Tenix Defence of Australia over a decade. Each ship

mutated slightly from its predecessor, so documents needed to be maintained

for early ships and altered slightly for subsequent ships. Government institutions

and large companies with special documentation needs use similar EDMS.

The Tenix technical writing team had a tall order: compile repair and maintenance data from suppliers and shipyards; format instructions to comply with contract specifications; track changes from ship to ship; and revise instructions during the 50-year life of the ships (Hall, Maintenance Procedures 239).

Since many systems were very similar from ship to ship, technical writers could reduce the workload if they could re-use information easily, but documentation began in 1990, before commercial EDMS were available. One important function needed would allow technical writers to change an item once and have the change propagate to the dozens of entries related to the item. As the database grew, the original software, DOS-based WordPerfect 5.1 merge tables, became unstable. When authors entered inappropriate or incorrect formatting codes or content the system often crashed, (Hall, Maintenance Procedures 239). The decision was taken to upgrade to a modern authoring and content management system and halfway through the project, in 1996, the entire document set was uploaded to a specially designed EDMS.

William Hall, documentation systems analyst for Tenix Defence on the Anzac project, led the conversion process. He found the existing merge tables could be transferred to XML (Extensible Markup Language) or SMGL (Standard Generalized Markup Language) environments with relatively little trouble. The team chose FrameMaker+SGML for their authoring tool as SGML allows documents elements to be tagged with certain content identifiers (Hall, Maintenance Procedures 240). That allows text to be manipulated within an electronic document delivery system (Bielewski & Boyle 120).

Once the authoring tool had been selected, the Anzac Ship team chose a locally developed repository system called Structured Information Manager (SIM). SIM was developed at RMIT University (formerly the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology) and is now commercially available as InQuirion (Hall email).

SIM is "a very powerful native XML database developed specifically to index, manage, and retrieve structured texts, combined with associated Web and supporting servers, and a powerful object-oriented programming and script processing language," (Hall, Maintenance Procedures 242). A SIM system was already in use in by a U.S. defense agency, so system capabilities and security were established (Hall email).

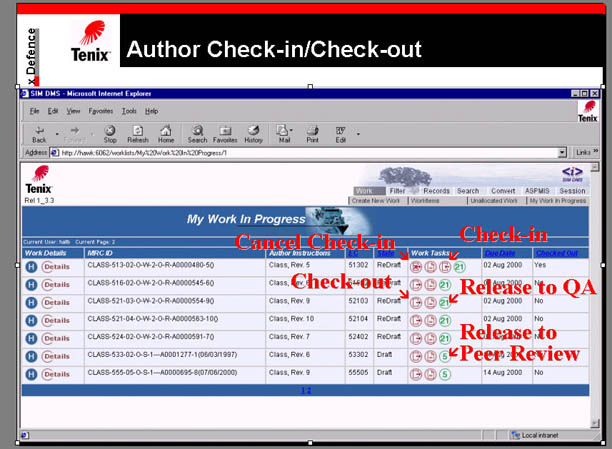

Anzac

Ship Project EDMS interface. Note that familiar terms are used so that the interface

is easily understood. (Image provided by William Hall)

Anzac

Ship Project EDMS interface. Note that familiar terms are used so that the interface

is easily understood. (Image provided by William Hall)

The benefits of using appropriate commercial software were seen immediately: Writers with no prior FrameMaker or SGML experience learned to use the system in a day and were fully productive within a week (Hall, Maintenance Procedures 243). The write-it-once capability reduced document management requirements by more than 80% and data delivery requirements by more than 95% (Hall, Maintenance Procedures 244).

From technical writers' perspective, using a system like that of the Anzac Ship Project is a dream come true. It is a state-of-the-art customized system built in consultation with the people who were to use it. Technical writers can prepare for working in similar environments by learning FrameMaker+SGML and as much as possible about XML and SGML. Coming out of an industrial EDMS environment like this, technical writers will have valuable experience using sophisticated EDMS as well as FrameMaker +SGML.

Applying the Information

Preparing for an Interview

Electronic document management systems

will likely become easier to use and more specialized. The best way to prepare

for working with a particular EDMS is to learn as much about the system before

starting on it by asking good questions in job interviews. Any technical writer

applying for a job should know as much about the organization's EDMS as possible,

and it is possible to make some educated guesses as to the type of system a

particular organization uses. Questions about the repository, authoring tools,

and any interfaces will demonstrate knowledge of the technical writing environment

and cannot help but make a positive impression.

Basic EDMS will be found in technology companies, no matter how small. At this level, the repositories will likely be simple to use and probably homemade, thus focus should be on authoring tools: the more types of authoring tools an applicant is familiar with, the greater value to the company. It might be useful to ask what software is used for authoring sales material, instruction manuals, and website content before moving on to questions on centralized server space for documentation.

Archival EDMS, often found in universities, may require little writing from the technical writer, but plenty of formatting and possibly editing skills. Unless the particular archive has been built in the last eight or ten years, manipulation of documents in the archive may be outside average skill sets. Research at university websites is probably the best way to get a feel for what academic archives look like. If applying for a specific job at an archive, it makes sense to visit the appropriate website for clues as to how the archive is built. Websites usually have email links to webmasters and a few well-phrased questions on the software being used might get a generous response.

Commercial EDMS, those sold by for-profit companies, are the most predictable in terms of configuration. FrameMaker seems to be the authoring tool of choice, but repositories could come from one of several companies, including IBM, Hummingbird, Ltd., iManage, Inc., or Documentum, Inc. Technical writers seeking employment at almost any company with a technical publications department should probably be as familiar as possible with FrameMaker and have researched repository makers' websites. Each repository company has a special name for its tools: Documentum 5, Hummingbird Enterprise, and iManage Worksite. Familiarity with these products and their uses can't help but impress interviewers, and there is plenty of information at company websites.

The largest commercial EDMS are in use at institutions such as government departments, up-to-date university projects, and major manufacturing and construction projects. Again, technical writers targeting companies with huge technical writing projects should learn FrameMaker and as much about XML and SGML as possible. In addition, research on customizable repositories would help in interviews. If at all possible find out what kind of document management system is in use at the targeted organization and research the provider via the web. Interviewers will probably not expect applicants to be familiar with specific repositories unless they were listed in the job posting, but a general knowledge of how repositories are used and the importance of naming conventions will show industry savvy.

Conclusion

EDMS developed as adjuncts to using

computers for computing, but the value of a centralized, well-managed repository

became apparent quickly. The combination of highly sophisticated authoring tools

and specialized repositories has launched a new era in technical communication.

Writers and editors can work on documents from anywhere in the world. Specialized

software allows technical writers to quickly create specialized documentation

on a scale impossible just a decade ago.

In commercial and industrial EDMS environments, technical writers are valuable for the skills they possess as well as the work they put out. Good EDMS make documentation cheaper to write and maintain, and companies recognize that fact. It is likely those who know how to construct and maintain large, active document repositories will be in high demand as EDMS are exploited by more organizations. Technical writers are likely to become subject matter experts on EDMS, thus the more knowledge gained on the subject, the more valuable a technical communicator is to the company.

References

Bielawski, Larry, Jim Boyle. Electronic Document Management Systems. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall PTR, 1997.

Hall, William P. "Maintenance Procedures for a Class of Warships: Structured Authoring and Content Management." Technical Communication May (2001): 235-247.

Hall, William P. E-mail to the author. 24 Mar. 2003.

Shopkow, Sara. Personal interview. 19 Mar. 2003.

West, Sharon. Personal interview via telephone. 29 Mar. 2003.

Lowe, Richard, Claudia Arevalo-Lowe. VAX information page 28 Mar. 2003 http://www.internet-tips.net/Misc/VAXhistory.htm>.

| Home | Portfolio | Services |

| Leisure | Contact | Site Map |